Lutiant LaVoye volunteered to serve as a substitute nurse during World War I with little to no training or nursing experience. As a recent graduate of Haskell Institute, an off-reservation vocational boarding school in Kansas modeled after Carlisle, she responded to the wartime labor demand and took the train to Washington D.C. in October 1918. A letter Lutiant wrote to a friend back home gives us a glimpse into life on the homefront at the height of the war and at the peak of the global flu epidemic.

“Really, they are certainly ‘hard up’ for nurses – even me can volunteer as a nurse in a camp or in Washington.”

-Lutiant LaVoye

The Context of Lutiant’s Letter

Dated October 17, 1918, Lutiant’s letter home to Kansas was written at a pivotal time in the war. The German offensive had stalled on the Western Front; peace negotiations were underway in Paris; and the armistice that would bring an end to the war would be signed less than a month later. The second wave of the worldwide flu epidemic was also reaching its zenith. This epidemic would take more lives than all of the battles of the Great War itself.

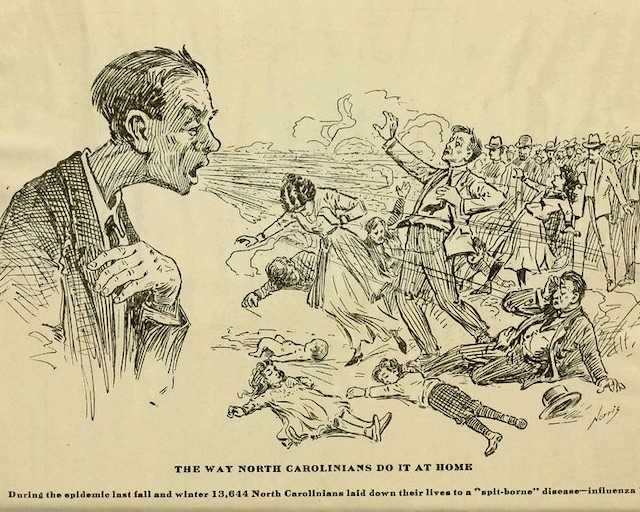

The Flu’s impact

An estimated 10 million soldiers died due to combat-related causes during World War I. Estimates of the number of soldiers and civilians who died due to the flu vary, but they range from 17 to 50 million.

“Really, Louise, Orderlies carried the dead soldiers out on stretchers at the rate of two every three hours for the first two days [we] were there.”

Lutiant LaVoye

Wartime government efforts to manipulate public information, in addition to the absence of a central data-reporting clearinghouse, help to explain the wide variation in mortality numbers. What is clear is that the H1N1 influenza virus claimed many more lives than even the conflict notorious for mass slaughter.

The Experience of the Flu

The first wave of the virus struck in the spring of 1918. As in previous experiences of influenza, most deaths occurred among infants and the elderly. However, that fall the virus mutated and struck with uncharacteristic virulence. The strain of influenza infecting the soldiers Lutiant cared for that October was unlike any other. The ‘W’ curve of the age distribution of deaths suggests that the healthiest of the U.S. population, men and women aged 15-35, became its frequent victims.

It struck quickly and without warning. Most victims died a horrible death within days.

“It was sure pitiful to see them die.”

Lutiant LaVoye

What began like any other influenza case, with a fever, sore throat and cough, abruptly turned deadly as the virus attacked its victims’ lungs. After contracting pneumonia, many eventually drowned in their own fluids.

Lutiant’s account spares us the gruesome details but leaves the reader with a vivid impression of the impact of the disease on its victims and those who cared for them. She tells her friend that after losing the first of her patients, she had to leave the ward and “cry it out.”

How Civilians Connected the Threat of War and the Epidemic

World War I and the flu epidemic do not simply occupy the same space on the timeline. They are undoubtedly intertwined. The degree to which each impacted the other is still being studied. Major world leaders—including Woodrow Wilson, George Clemenceau, and David Lloyd George—all contracted the virus while attending the peace conference. The letter from Lutiant alludes to rumors on the American home front that linked the war to the flu.

Lutiant mentions having seen silver screen celebrities Douglas Fairbanks and Geraldine Farrar during the Fourth Liberty Loan campaign. She writes of rumors that the flu was hampering the effort to sell war bonds to finance America’s military expenditures.

“All the schools, churches, theaters, dancing halls, etc. are closed here also.”

Lutiant LaVoye

She devotes a paragraph to the possibility that Congress might furlough war-related workers until the flu subsides. She laments that she wasn’t able to climb up inside the Washington Monument for a view of the capital, as it was closed due to the flu. Although she doesn’t make a direct connection to the public closures and the reduced war bond sales, students of history who analyze this primary account are sure to bring the question to mind.

Another rumor Lutiant relayed to her friend in Kansas shows one perhaps dubious connection civilians drew between World War I and the flu epidemic.

“Two German spies, posing as doctors were caught giving these Influenza germs to the soldiers and they were shot last Saturday morning at sunrise.”

Lutiant LaVoye

Claims of enemy espionage were common on the homefront. Whether there is any truth to this particular accusation or not, Lutiant’s belief that Germans were purposefully engaging in biological warfare on the homefront demonstrates that ordinary Americans saw the threat of the flu as connected to the threat the Germans posed. All sides in the war used the epidemic to boost public resolve to defeat the enemy. The nomenclature used in contemporary publications aligned the flu with the antagonists. Depending on which side you were on, you might have called it Spanish Flu, Flanders Fever, the Grippe, Bolshevik disease, Kirghiz disease, White Man’s Sickness, Kaffersiekte (Blacks’ Disease), Chinese Flu, Purple Death or Sand Fly Fever.

The Value of a Personal Account

Thankfully, Haskell Institute was affiliated with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, so Lutiant LaVoye’s letter has been preserved. Personal primary accounts like hers provide such rich insight into the lives of the people who walked through the things we study. Lutiant writes of her everyday life. She is aware that many are dying, but unaware that she is witnessing one of the largest epidemics in recorded human history, second only to the Bubonic Plague. The weather is cold, and Lutiant asks her friend to send her a sweater. She is intrigued by the novelty of a nearby airfield. She is interested in spending time with a fella. In fact, she devotes nearly two pages to the guy.

Her letter helps humanize the war and prompts many questions about Lutiant’s earlier and later life. Did she herself ever contract the flu? Did she survive the war? Who were Miss Keck and Mrs. McK? Why does Lutiant say of them, at the beginning of her letter, that she wishes that they would contract the flu and die? Lots of questions come to mind after we read that remark. Just how bad were Lutiant’s experiences at the Indian boarding school in Kansas? Were those experiences shared by many students, or unique to her? Does she come off as flippant and unkind because her experiences at the school and at the hospital have traumatized her? And of course, did she continue seeing the charming soldier she met at the train station?

Vince Bradburn, the 2015 James Madison Fellow from Indiana and a 2020 graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government, teaches social studies at Shelbyville High School.