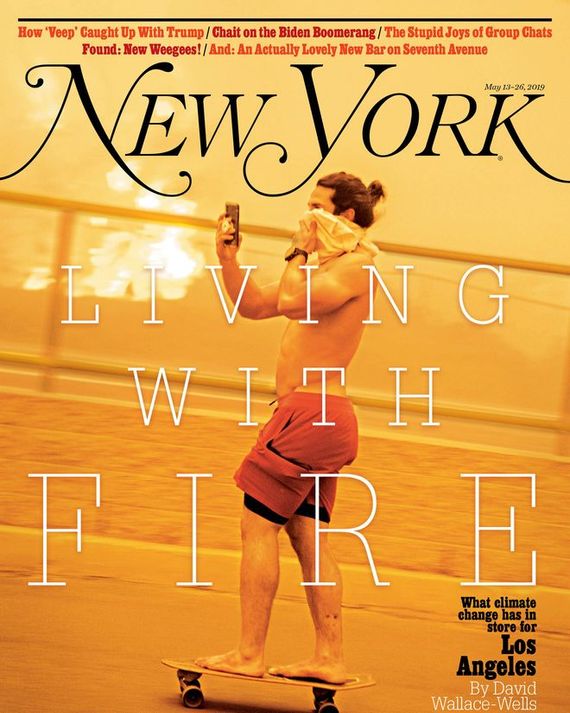

In 2019, David Wallace-Wells wrote a cover story (“Living With Fire”) warning of the fires to come in Los Angeles based on the fall 2018 fires that surprised many Angelenos.

“No one will ever be honest about this, but firefighters have never stopped a wildfire powered by Santa Ana winds,” the environmental historian Mike Davis told me earlier this spring, as we toured hills ravaged by past fires and — redeveloped and reinhabited in their wake — haunted now by future ones. “All you can hope for is that the wind will change.”

Already, the fires are different. Cal Fire used to plan for wind events that could last as long as four days; now it plans, and enlists, for 14. The infernos bellowed by those winds once reached a maximum temperature of 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit, Cal Fire’s Angie Lottes says; now they reach 2,100 degrees, hot enough to turn the silica in the soil into glass. Fires have always created their own weather systems, but now they’re producing not just firestorms but fire tornadoes, in which the heat can be so intense it can pull steel shipping containers right into the furnace of the blaze. Certain systems now project embers as much as a mile forward, each seeking out more brush, more trees, new eaves on old homes, like pyromaniacal sperm seeking out combustible eggs, which lie everywhere. In at least one instance, a fire has projected lightning storms 21 miles ahead — striking in the right place, these ignite yet more fire. “California is built to burn,” the fire historian Stephen Pyne tells me. “It is built to burn explosively.”

Source link