Katherine Thrailkill considered careers in drama, law, and hi-tech sales before realizing all her interests and experiences pointed her toward teaching social studies. She would help students gain political efficacy—the knowledge and confidence they need to make their voices count in our political system. Once she found her calling, colleagues helped her make her way. A key mentor was Nancie Lindblom, who showed Thrailkill how to model civil discussion. Lindblom is the 2013 Arizona Teacher of the Year and a 2014 Graduate of the MAHG program.

Thrailkill was a third-year teacher happily settled at Skyline High School in Mesa, AZ, when Lindblom phoned to ask her to apply for an opening at nearby Mountain View High. The request surprised and flattered Thrailkill. Not only was Mountain View the high school from which she’d graduated; Lindblom was a teacher she admired. While earning her Masters in secondary school education at Arizona State University, she’d observed Lindblom’s class. “That’s the teacher I want to be,” she’d thought.

Lindblom’s “Defining America” Course

Thrailkill watched Lindblom teach a sophomore course she herself designed: “Defining America: The Fulfillment of the Promise of the Declaration of Independence.” Lindblom based it on a summer seminar she attended in the early 2000s: the Presidential Academy, a forerunner of Teaching American History’s current programs. The three-week program took teachers from across the country on a study tour of Philadelphia, Gettysburg, and Washington, DC, discussing with leading scholars three eras in history—the Founding, the Civil War, and the mid-twentieth century Civil Rights movement—all of which tested Americans’ commitment to their principles of liberty and equality. This inspired Lindblom to design an elective sophomore course on the same three periods, using many of the primary documents she’d studied in the TAH seminar. The course would prepare students for her fast-paced junior-level AP American History class. It would give them time to think about American principles while learning to read primary documents.

As Lindblom posed questions that pushed students to think through the readings, Thrailkill was reminded of her favorite undergraduate courses. A political science and philosophy double major at Arizona State University, Thrailkill learned about the American political system in large lecture halls. But small seminars on ethics and political philosophy stimulated her imagination and taught her to think critically. Lindblom’s teaching approach “was everything I wanted to do.”

How Lindblom Modeled Civil Discussion

She took the job at Mountain View. The next year she taught across the hall from Lindblom. Thrailkill watched Lindblom model civil discussion, disarming students’ fears of disagreeing with others. Increasingly reliant on cell-phone communication, today’s students often feel “anxious” when asked to debate historical or political questions, Thrailkill said. Teachers must model civil discussion. “Before challenging another person’s argument, you have to understand it. You must listen to what they say, then tell them what you heard, to verify that you understood.” This not only shows respect for the other person; it pushes you to carefully think through your own position. She found students learned this process best in small groups; afterwards, they more comfortably discussed issues with the whole class.

Lindblom, a 2011 James Madison Memorial Foundation Fellow, recommended that Thrailkill apply for the same grant, to fund a Masters emphasizing constitutional studies. She also recommended the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) at Ashland University as the ideal MA program for a working teacher interested in encouraging civil discussion of the perennial issues in American civic life. Thrailkill applied twice, and when she learned in May that she’d been awarded the grant for 2024, she felt Lindblom’s recommendation had made the difference. Looking through the Masters study options the Madison Foundation recommended, Thrailkill quickly concluded that Lindblom’s choice was the best.

Thrailkill’s First Impressions of MAHG

She registered for two courses in this year’s summer residential MAHG program. A study of Cherokee Indian removal during the 1830s would inform her on a part of history she knew little about. A second-week course on the American Founding would help her review what she’d learned as an undergraduate about the framing of the Constitution.

Teachers in the course on Cherokee history participated in a “Reacting to the Past” game, testing whether the discovery of gold on Cherokee lands make their forced displacement into the Arkansas territory inevitable. Each player acted the part of an actual historical figure or a composite of several, basing their actions on primary documents they’d read and discussed. Some played Cherokee nationalists, vowing to hold the land guaranteed them by federal treaties; some, white political leaders determined to force them off their land. Others played Cherokee leaders who thought the tribe’s survival depended on accepting removal. A fourth group represented Cherokee who were undecided.

Most players made one or more speeches in character. Professor Jace Weaver assigned roles only after asking the teachers how comfortable they were with public speaking. Having begun college as a drama major, Thrailkill told Weaver, “I’m fine with any role you give me.” She got the role of Andrew Jackson, the historical character she most loves to hate. Presiding over a fictional meeting between representatives of the Cherokee and the white officials advocating their removal, she delivered a gracious speech of welcome that conceded none of the Cherokee claims.

The game illuminated the primary documents Thrailkill read to prepare for it. It helped her understand why Cherokee removal occurred, despite its evident injustice and the Supreme Court ruling in Worchester v. Georgia. Thrailkill now plans to use more role-playing exercises in her teaching. They make classroom debate “less risky. No one will judge you for taking Andrew Jackson’s side against the rights of Native Americans. You’re acting! Yet the exercise requires you to think about Jackson’s perspective.”

The course on the founding, taught by Professors David Alvis and Beth L’Arrivee, revealed the tense conversations that led to our constitutional framework. Delegates compromised without necessarily resolving their underlying differences. Thrailkill confided she’d “been feeling a little low lately about political efficacy.” Citizens seemed doubtful that they could make their voices heard in our polarized political climate. Given all that the founders achieved in the summer of 1787, Thrailkill “expected to come out of this course feeling a little more cynical” about current politics. “But now, I see that today’s debates reflect older ones.” The Antifederalists foresaw the elastic potential of the commerce and the “necessary and proper” clauses; our current debates over taxation and federal regulation reflect their worries. Yet the founders thought through their reasons for incorporating these and other more controversial provisions into the Constitution.

Building Students’ Political Efficacy

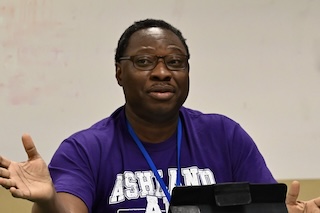

“I absolutely love MAHG,” Thrailkill said, impressed with the quality of the seminar conversations. The program will equip her for her life’s work of building students’ political efficacy. With the help of veteran teachers like Lindblom, Thrailkill is well positioned for the task. She advises Mountain View’s Model UN team; students on the team take her AP Comparative Government class. They study the governing systems in six nations: Mexico, whose system is modeled on that of the US; the United Kingdom, with a parliamentary system, and Nigeria, which is considering returning to such a system; the authoritarian systems in Russia and China; and the theocratic system in Iran. The team debates other teams in district, state, and sometimes national conventions. Thrailkill is constantly building the knowledge she needs for the course. She shared a shuttle ride from the airport to the Ashland campus with Henry Adeoye, a Houston-based, Nigerian-American teacher and Madison Fellow. Born to the Yoruba tribe, Adeoye engaged the Nigerian driver—an Igbo—in conversation about the differences between the Nigerian and American political systems. Thrailkill planned to tell her students about their conversation.

During the 2022-2023 school year, Lindblom designed a new sophomore course — “Changemakers” — to teach civil discussion and build students’ political efficacy. Then she was offered the position of social studies curriculum advisor for the large Mesa Public School district. Lindblom asked Thrailkill to take on the class. Working with a veteran English Language Arts specialist (who also has become a mentor), Thrailkill implemented the double-unit course last year. It challenges students to think about how political and social reforms occur; teaches critical reading and media literacy skills; informs them on Constitutional protections for free speech; and teaches civil discussion through “structured academic controversies”—debates that require participants to restate their opponents’ arguments, conceding the strongest points, before responding. Students also select problems to research, investigating policy solutions and presenting their findings in a forum at year’s end. “Nancie attended the forum and said we did well. A few days later I learned about the Madison fellowship,” Thrailkill said. “I’ve been blessed with brilliant and generous mentors. I feel like I won the teacher lottery!”